Moy Sutherland – Curator’s Choice Spring 2022

blog

“For me, the meaning of life is to learn of and understand my cultural surroundings, so that this knowledge can be preserved and used in everyday life. Like our elders before us passed this knowledge on, so must we to our descendants. In this manner, respect becomes an integral part of life, respect for everything. I draw my knowledge and inspiration from the teachings of those whom I respect, and I incorporate these into everything I do.” – Moy Sutherland

Within First Nations culture, it is believed that everything that exists is deserving of respect and has earned its place in the world. “Let us respect everything” is essential to the interconnectedness between the land, the elements, celestial beings, creatures both natural and supernatural, and humanity.

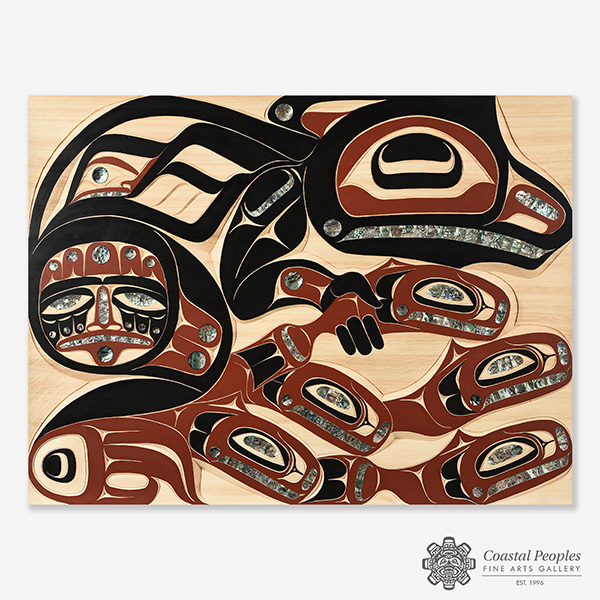

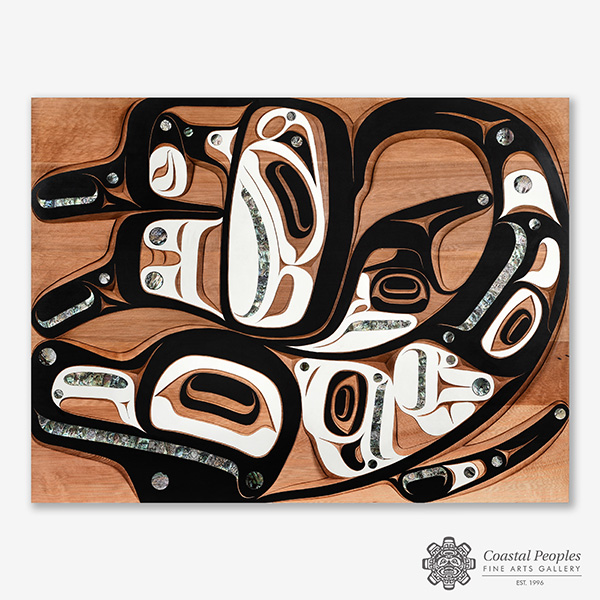

Moy Sutherland beautifully illustrates this powerful connection throughout his designs and, by combining the strength of cedar wood from the land with the brilliancy of shells from the ocean, they come alive for us. Its energy and light flows through his dynamic shapes and formlines onto various decorative and ceremonial objects that are both traditional and contemporary.

Nuu-chah-nulth artist Moy Sutherland’s pieces are shaped by his respect for the interconnectedness of all things – natural and supernatural, earthly and celestial. His art cherishes the cultural teachings of his forebears as well as the knowledge and insights of the master carvers with whom he apprenticed, including Art Thompson and Carey Newman. Sutherland works across many media and scales, from totem poles to gold jewelry, and is especially admired for his cedar carvings inlaid with abalone and operculum shell.

YOUTH CARVE OUT A BOND WITH FIRST NATIONS CULTURE

Written by Travis Paterson | Reporter at Saanich News | March 31, 2016

When Moy Sutherland led the raising of the third and final totem pole in front of the Native Friendship Centre last Thursday, he didn’t see it as the end of a project, only the beginning.

Sutherland’s voice boomed through the mic as he guided more than 100 youth and members of the community who lined along Regina Avenue in front of the centre. Slowly, they pulled the 6,000-pound Qweesh-hicheelth pole with a 200-foot-long rope, hand-over-hand, through a pulley until it stood straight. It stands beside two other totem poles as all three nations of the Island are represented, the Nuu-chan-nulth nation of Western Vancouver Island, the Coast Salish (Southern Island) and the Kwakwaaka’wakw (Eastern Vancouver Island).

“There’s lots of room out here for more, this is not the end,” Sutherland said. “When we made this, we also started an army of new carvers.”

The pole carries many tales of Nuu-chan-nulth legend. At the top, a thunderbird transforms into a human, while at the bottom, a killer whale transforms into a wolf. The wolf’s head is situated where the whale’s blow hole would be, and within that is a human figure, representing the Wolf Society, a group of Nuu-chan-nulth warriors who would deal with the dead, organize funerals and act as police.

Qweesh-hicheelth is Nuu-chan-nulth for transformation, and Sutherland, who is Nuu-chan-nulth, sees the transformation that’s happened throughout the project, and beyond. In September, the 42-year-old master carver and artist started alone, trimming the massive red cedar from Ehattesaht (in Esperanza Sound) into a flat-back totem pole, 26 feet long. In November, he took on a crew that included at-risk youth who knew nothing of carving, and spent the past four-and-a-half months teaching them, and together they completed the project.

“This was all about empowerment for youth from the start,” said Sutherland. “We used hand tools, and it slowed the process, but at the end I could say ‘go carve this area flat,’ and they would know how to do it.”

All the tools were hand made by “Iron Jake” James, the Metchosin blacksmith who also anchored the finished pole to its cement base. Sutherland then ordered a set for each member of the team, and gifted them upon completion.

“There were a lot of cuts to begin with,” Sutherland recalled.

As a teen, Sutherland left his home in Gordon Head for a life on the streets. Instead of Lambrick Park secondary, he spent the ages of 13 to 20 learning a different life.

“I didn’t carve anything until I was 19, that was a start,” he said. “There was something about when you finish something, and everyone appreciates it, that was very fulfilling.”

Through art, Sutherland learned the cultural history of his people. And now he encourages youth to explore the history of their own people.

“I tell them, go learn, and let’s stand that up [as a pole].”

One of the crew members was Tejas Collison, 24, who didn’t expect to work on the pole. Collison lives in Esquimalt and is apprenticing with master carver Carey Newman, who built the first two poles at the Friendship Centre. Collison actually worked on the Coast Salish, which was raised in 2014. So when it came to crunch time, Sutherland put the word out, and Newman assigned Collison to help out.

“I tried to assist where need be with sharpening of tools, sanding and other rudimentary skills, and focused on the features of the killer whale,” Collison said.

It’s that kind of team mentality that has Travis Peal, 33, excited to carry on.

After years in the Canadian Navy, Peal left to study electrical training at Camosun College. He recently finished his studies but without work, he visited the Native Friendship Centre one day looking to volunteer.

A member inside of the Friendship Centre told Peal there was a project going on out back.

“I talked to Moy and literally threw my bag down and started carving,” Peal said. “It was a lot better than waiting for the phone to ring.”

The experience ignited Peal’s ‘inner-native.’ He’s from the Nisga’a village of New Aiyansh but after years in the Navy, then in college, he hadn’t been around a First Nations culture to speak of.

“I appreciate the way we all connected on the project, and the way that I connected with my own cultural history,” Peal said. “It’s why the Friendship Centre is here, for Natives from anywhere in Canada to connect with each other.”

Sutherland’s vision has now moved from building a totem pole, to erecting a traditional big house on site at the Friendship Centre, instead of the tent used by Newman and himself.

“A place to store tools, and for this crew to carve, and to train more to carve. There’s no place around to train carvers, so let’s do it here.”

To view Moy Sutherland’s entire collection in our Gallery and for more details, please click here.